Neobladders, who knew?

I’ve done a LOT of anatomy. Almost nine years of managing the Human Anatomy department of a major Canadian medical school - and all that entrails, I mean entails - I’ve seen hundreds of cadavers, each with normal, slightly abnormal, or really abnormal anatomy. Everyone’s just a bit different. Sometimes they’re born with it and probably lived their whole life without even knowing it, like partial or even complete situs inversus (a left-right flipping of the internal organs). Mostly, though, the weirdness is iatrogenic, meaning it’s caused by some “corrective” medical intervention at some point during their lives which leave lots of tell-tales. Couple that cadaveric / pathology experience to this medical illustration gig that I’ve done for close to twenty years, plus my day job consulting on medical device designs, and I’ve seen some odd anatomy/pathology and even more odd procedures to correct it. It’s always kind of mind blowing for me think of the first surgeon somewhere solving a problem by replumbing the ailment with what’s available to them within the same body, thinking to themselves; “If I take this blood vessel from over there, take a piece of fascia or pericardium from here, suture up a pocket, and plug this into that…yeah! It should work!” That’s not usually how things happen in medicine or surgery as things are so incremental and slow, but still, what kind of chutzpah must we have to even try them? Subsequently for patients, it’s kind of amazing what people can adapt to and live with, like Fontan circulation into your twenties!

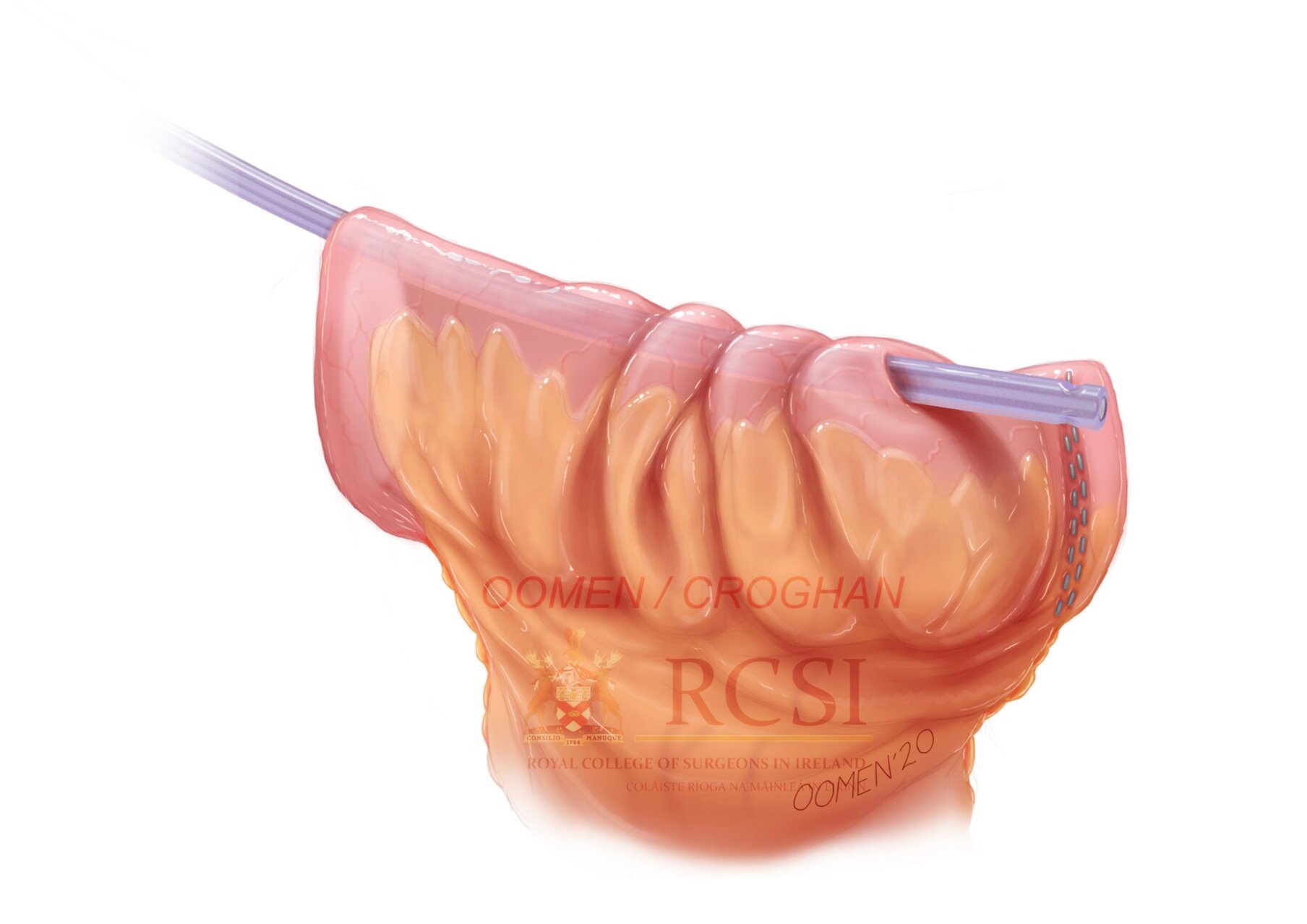

Neobladders: start with one little bit of distal small bowel and two ureters, spatulated and freed from their retroperitoneal hiding place.

A Yankauer suction tube is pushed through a perforation in the bowel to use as a guide for a catheter and guidewire.

Given all the above, I never once stopped to think of what happens when a person has bladder cancer, or some similar problem , requiring complete cystectomy. Afterwards, where does the urine go? I mean, where does it go before going through a urostomy and into a bag? And what happens to the ureters? And how does it all stay patent? Stents? Does glomerular filtration work best with a bit of back pressure , or…?Infections? Prolapse? So many questions I never knew I had.

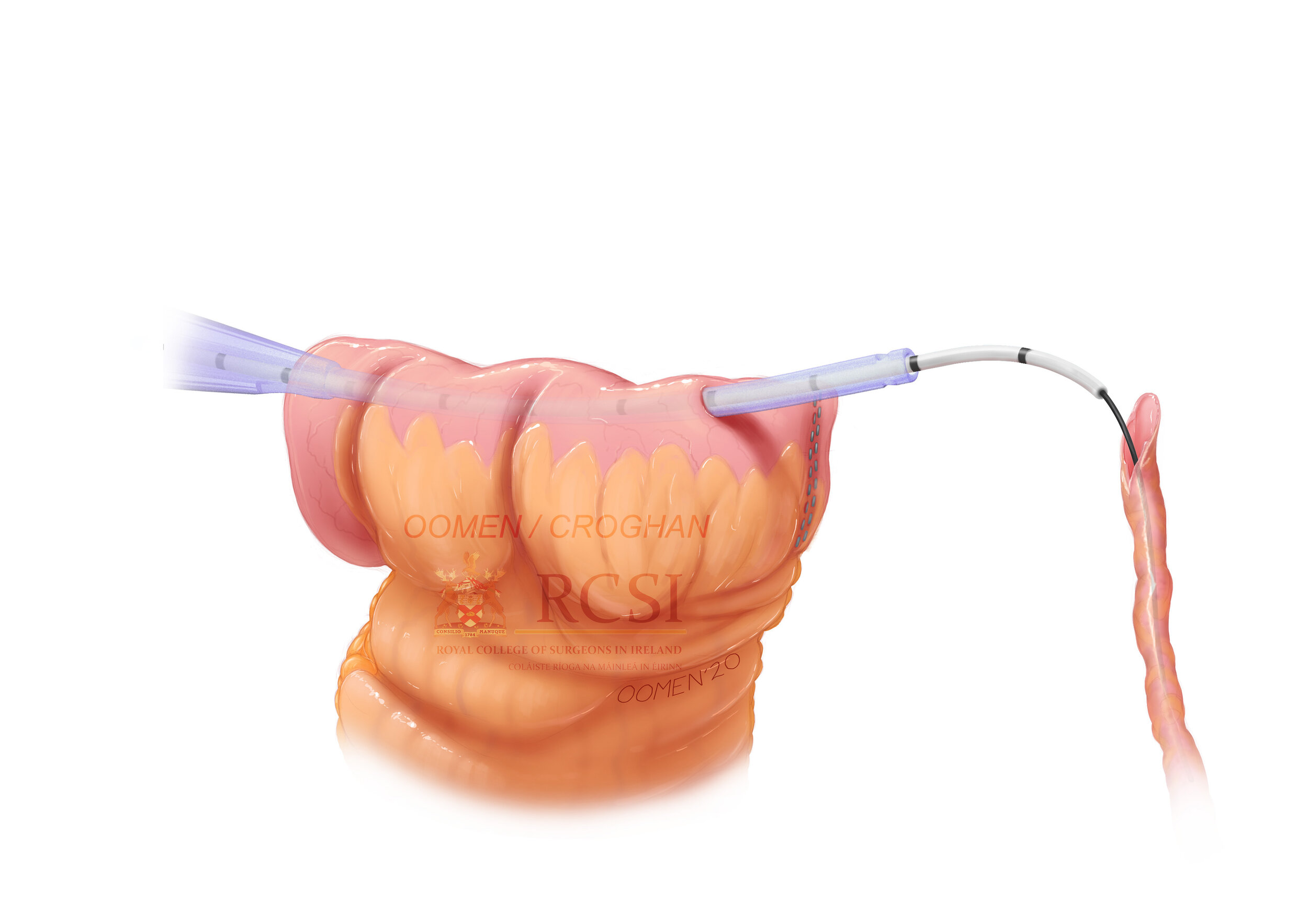

The spatulated ureter is slid over the guidewire and catheter.

Until one day this summer I got a request to illustrate a “neobladder” procedure. To be honest, it happened in the opposite order: I didn’t have any of these questions until I got the request. My client, a Urologist at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) in Dublin was almost too happy to answer them all in detail. I almost never pass up the opportunity to do surgical sequences and learn something new. They’re easily my favorite things to illustrate with fantastic opportunities and challenges to use everything in my illustrator/animator/designer toolbag to tell a story: squash, stretch, transparency and translucency, lighting, colour, a little bit visual trickery here and illusion there to show tension, pressure or compression. It’s all good fun in the service of science and medicine and I’m one lucky fellow to both get to do it and be able to do it.

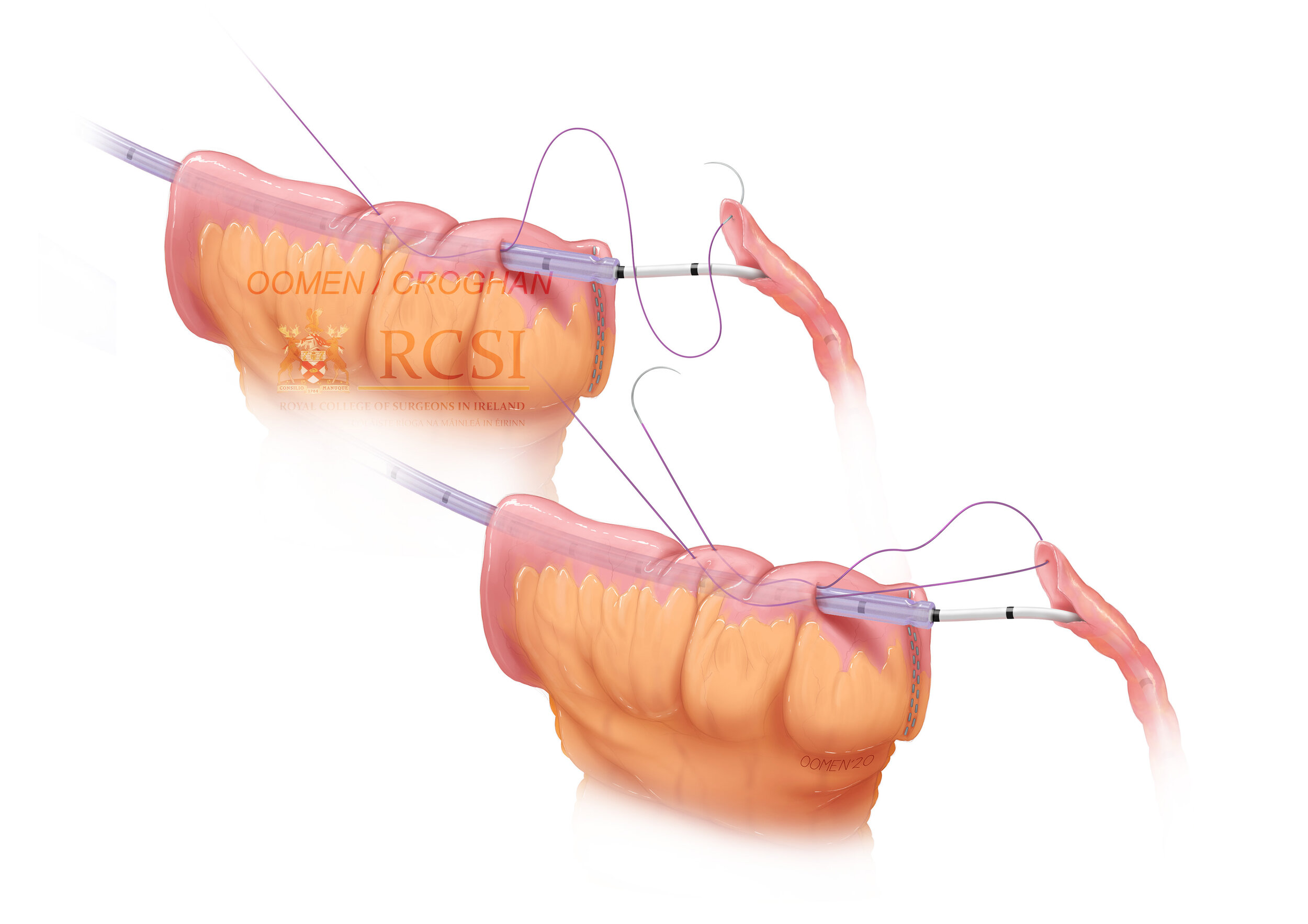

A suture is used to draw the spatulated ureter over the catheter and into the bowel, where it is secured

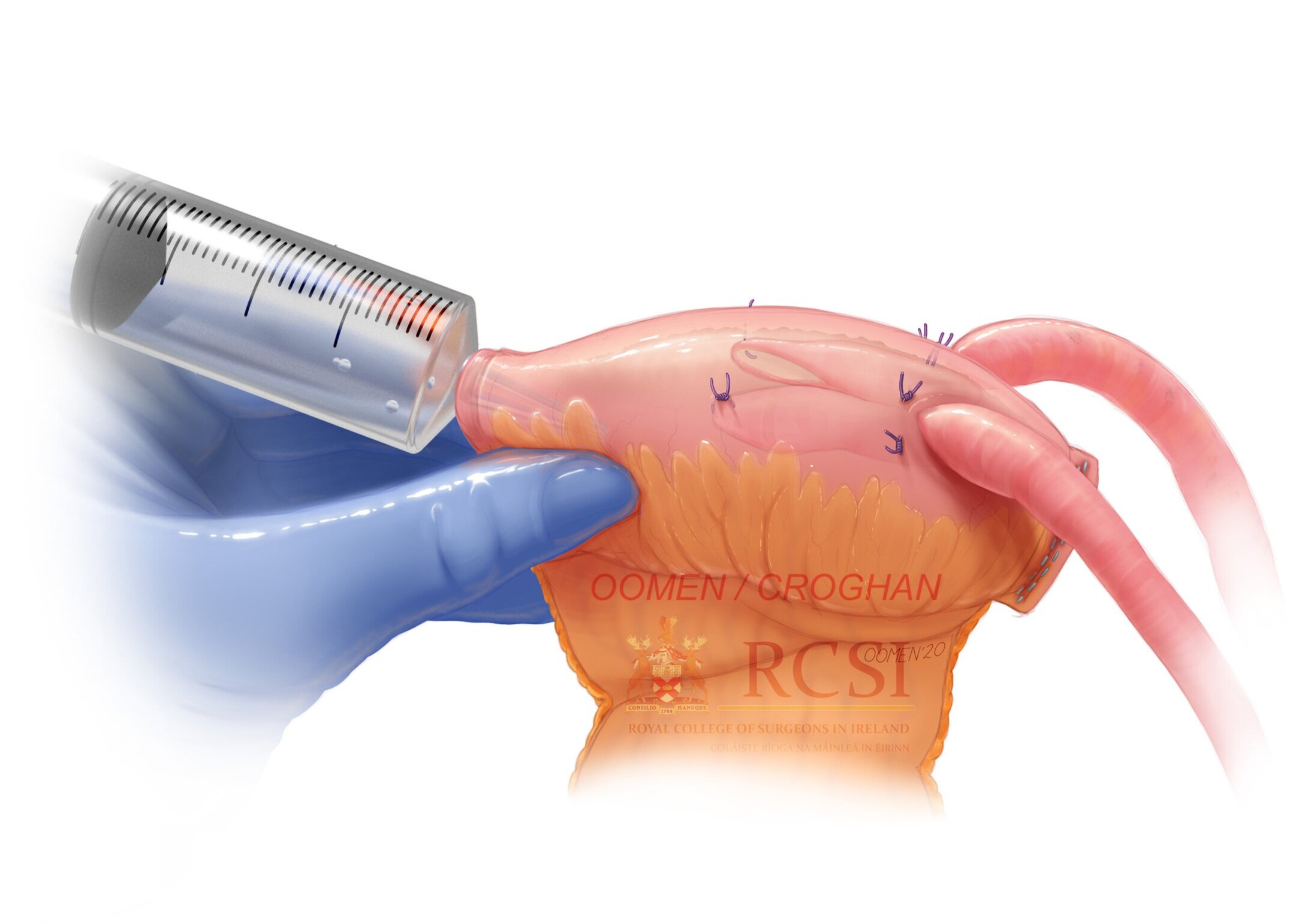

Turns out you make a new bladder; a neobladder, if you will, and you make it out of bowel. A little piece of distal jejunum is taken out of the intestinal tract and pulled aside. The remaining jejunum is anastomosed back together, while the little piece in question has one end sutured up and the ureters plugged into it. This little pocket is then sutured to the abdominal wall where a urostomy is formed into it. There’s apparently a few techniques for doing this little maneuver, and the one I was working on was a relatively new trick involving using suction tubes and catheters to help with pulling the ureters into position. I have to admit, I was a bit disappointed that this neobladder didn’t just become a defacto new bladder, fixed into the pelvis with the urethra plugged into it. But then, actual bladders are pretty remarkable in their general stretchiness, and in their natural anatomical valves that keep a healthy person from neither peeing themselves constantly, or even having to make a conscious effort to not pee themselves. Tough to reconstruct that and the innervation one needs to actually know they need to pee in the first place.

The human body is a wonderous thing, bladders neo, new, old, and all.

The completed neobladder is pressure tested before being sutured to stoma opening to create the urostomy.